Ministering to the poor

by Robert Jeffery

Looking back to the origins of The Salvation Army, many people are quick to point out that it wasn’t William Booth’s intention to start a church. This is an overstatement of the truth. We could with more accuracy state, it was not Booth’s intention to start a mere charity to the poor and downtrodden. As a teenager, Booth cut his teeth on evangelism by conducting cottage ministries and holding services in people’s homes. Later, as a young minister in the Methodist New Connexion, with his wife Catherine by his side, Booth saw his calling in revival preaching, mirroring his heroes Charles Finney and James Caughey, founders of the transatlantic revival movement. Preaching, evangelism, and soul winning was the spiritual food that William Booth lived on.

We know that somewhere in the transition from the Booth’s Christian Mission to The Salvation Army, a concern for the poor’s temporal relief, along with their spiritual salvation, became a winning combination for the Army’s growth around the world. “Soup, soap, salvation,” a simple phrase that is profound in its logic, was born out of a change in the Booth’s approach to ministry.

One of the great written texts of The Salvation Army that reflect this new direction was Booth’s 1889 article, “Salvation for Both Worlds.” Historian Dr. Roger Green writes, “The Booths always preached personal salvation by faith in Christ; that commitment never dimmed. Nevertheless, by 1889 William was convinced that salvation also had social dimensions. Redemption meant not only individual, personal, and spiritual salvation, but corporate, social, and physical salvation as well.” In Booth’s own words, “As Christ came to call not saints but sinners to repentance, so the New Message of Temporal Salvation, of salvation from pinching poverty, from rags and misery, must be offered to all.”

Among the first ministries of the Salvation Army aimed at reducing poverty was the overnight shelters, birthed out of the story of Booth’s stern command to his son Bramwell to “Do something!” after seeing dozens of homeless men sleeping under a bridge. Remember in Charles Dickens,’ A Christmas Carol, when Ebenezer Scrooge cruelly asks the charity workers who knock on his door, “Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?” His question, though birthed out of meanness, was probably how many upper-class Londoners felt about the poor of their day.

The Victorian era poorhouse was truly a place of last resort for the indigent masses. The poor were in fact punished by being sent there, made to work long and hard hours, sleeping in overcrowded and dirty dormitories. By contrast Salvation Army shelters were clean and relatively comfortable. Guests were given good food and hot tea and were always offered an encouraging word by the officer staff. Religious services were offered, but they were never a condition of receiving aid, a Salvation Army principle still in practice today.

George Orwell, one of the greatest writers of the 20th century, stayed in a Salvation Army shelter as a young man. He detailed the experience in his book, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933). Though he doesn’t write a particularly positive account, he does acknowledge the need for such places when he writes about a man being admitted to the Salvation Army shelter who was in the early stages of starvation.

Perhaps the greatest ministry to the poor birthed out of The Salvation Army in those early days was the service of the “Slum Sisters.” These were women officers, who took off their formal uniforms to wear the apron of service; not in service to the wealthy but offering their labor to the poorest London neighborhoods. The Army was born during the height of the Industrial Revolution. Rural families flocked to the larger cities to take jobs in factories. It was a time of massive social upheaval, and not every family remained intact. East London was full of neighborhoods where single women struggled to raise children on their own. Salvation Army Slum Sisters literally moved into the neighborhood to help these marginalized families.

In the U.S.A., The Salvation Army became a force for good in helping the poor. The Industrial Revolution in the United States caused many people to leave the family farm to pursue a life in the city. Cities such as New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Philadelphia were experiencing explosive growth due to immigration and migrating rural Americans. While some experienced a better life with more amenities, many endured severe hardships as the expanding cities struggled to secure housing for their growing populations.

The America that George Scott Railton and the seven Hallelujah Lassies arrived in (1880), and the Shirley family before them (1879), was a land of contradictions. It was the height of the Gilded Age where families like the Astors, Rockefellers, and Vanderbilts were amassing fortunes never seen in human history. Yet, just a few miles away from Millionaire’s Row, hundreds of thousands of people were experiencing grinding poverty. Even those fortunate enough to be employed often had to work and live in deplorable conditions that were neither safe nor sanitary. Do an online search of Jacob Riis’ photo anthology “How the Other Half Lives,” from 1890, and you will learn of the terrible sufferings endured by America’s poor.

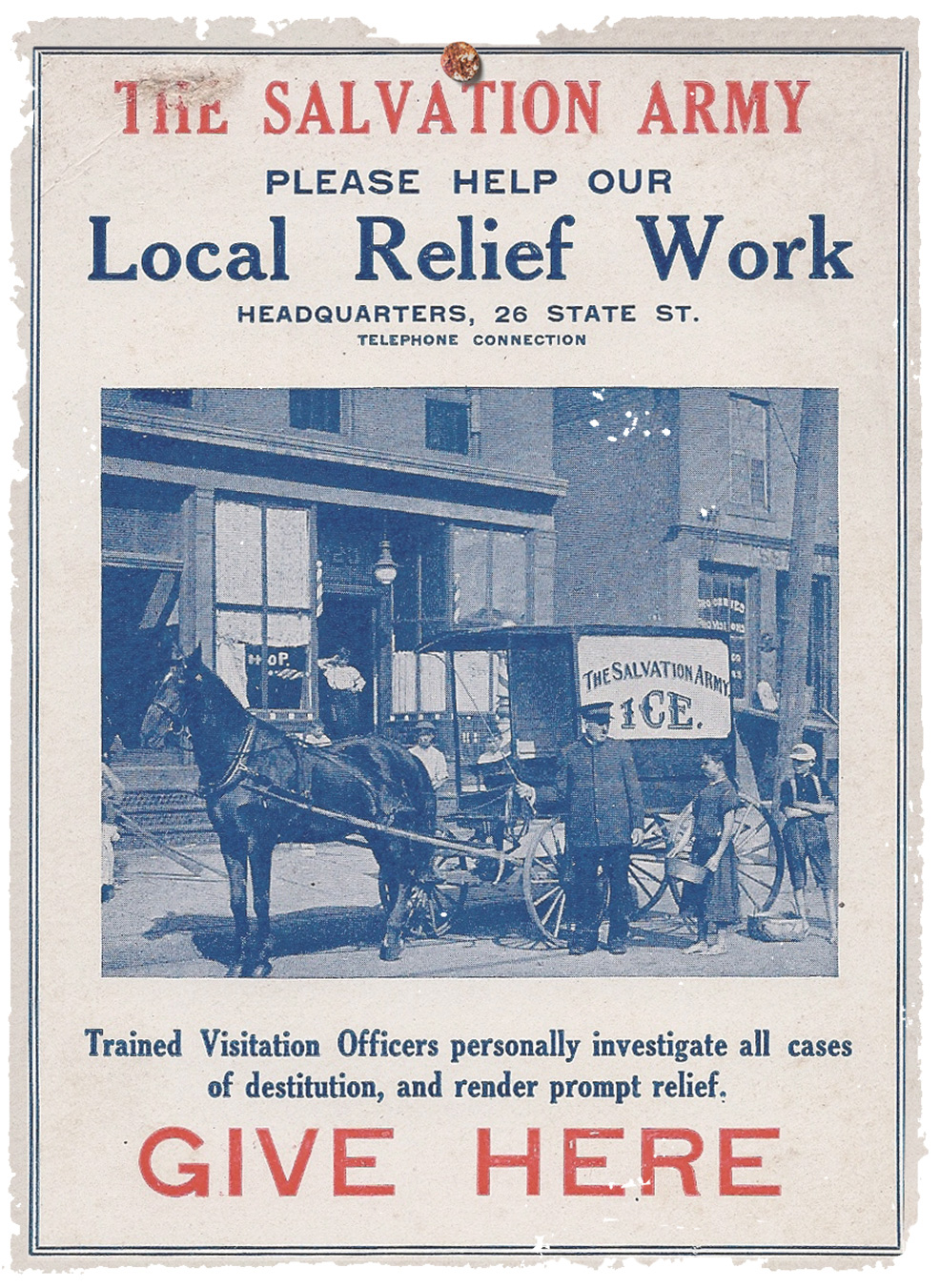

Though early Salvation Army efforts in the U.S., were largely evangelical, as the movement got established, they turned their efforts to combatting poverty. In the cities of the northeast, two popular frontline relief services included the giving of coal in winter and blocks of ice in summer. This effective ministry persisted for many years until more modern heating and refrigeration technologies made them redundant.

Farm colonies were experimented with and were effective for several years in teaching urban families how to use the land. The Industrial Homes and Depots, envisioned in William Booth’s In Darkest England book (1890) gave people skills in salvage and reclamation, allowing them to move into successful trades and earn an income.

Jesus said, “The poor you will always have with you (Matt 26:11).” Affirming these words, our founder William Booth, seeing the desperate masses of London’s east end proclaimed, “These are our people.” More recently, a Salvation Army resource from 2017 said, “The Salvation Army seeks to walk alongside people who are struggling against the long-term effects of extreme poverty in their communities and in their lives. Many members of The Salvation Army are themselves living in extreme poverty. This is not something we do just for others; in many places, we are the poor.” However one chooses to emphasize it, God calls us to be in community with the poor. May we always be faithful in our obedience to this divine command.

Read more from the latest issue of SAconnects.