One in Christ

by Colonel (Dr.) Janet Munn

A historical account of gender equality among evangelical church leaders of the Wesleyan—Holiness movement.

I was born and raised in the Church of the Nazarene, where my mother, though not in “ordained” ministry, was a powerful spiritual influence, and gifted at discipling countless individuals throughout her short life.

My father, who was an elder in that same denomination, treated me, his only daughter, with great respect, communicating to me in mostly unspoken ways, that I was intelligent, competent, and capable. Both my parents, formed in this church of the 19th century Wesleyan–Holiness movement, established in my young heart a foundation of confidence, and an expectation of gender equality, that remains today.

My first intersection with The Salvation Army was as a teenager, working at a summer camp for underprivileged children in greater Boston, Mass., at the Army’s Camp Wonderland. It was there that I first encountered women who were gifted for, and had access to church leadership. They were women preachers, women making decisions for the organization, dynamic women. This left a lasting impression on me, one that was reinforced many times, with redemptive effect, in the ensuing years.

As a young adult, when I was considering the best way to offer my life in service to Jesus and the world, The Salvation Army, having become my community of faith, was the obvious choice. After the necessary course of study and preparation, I was commissioned and ordained as a Salvation Army officer in 1987, with a full commitment to serving the Lord. And so, I have, ever since.

Freedom, the Wesleyan way

At the time of this writing, it has been 285 years since John Wesley reluctantly attended a Moravian meeting in Aldersgate Street, London, UK and found his “heart strangely warmed.” This experience of a deep inner assurance of God’s love was life–changing for Wesley, and as a result, for millions of others who followed him.

Wesley was profoundly formed intellectually and spiritually through the remarkable influence of his mother, Susanna Wesley, who gave birth to 19 children. Her life and journey shaped the millions of descendants of Methodism, including The Salvation Army, in ways we see today.

The Rev. Alfred Day, Methodist archivist and historian observes, “We see in [Susanna] and in her sons this tension between Puritan evangelicalism and Church of England prayer book order, spirituality and sacramentalism. Long before women were ordained, Susanna would sometimes gather friends around the kitchen table and lead prayers when her preacher husband was away. She kept the parish going in his absence.”

The World Methodist Council is made up of 80 Methodist, Wesleyan, and related Uniting and United Churches representing over 80 million members in 138 countries.

All of whom have descended directly or indirectly from the religious influence of John Wesley. Further, many female clergy today have roots in Wesleyanism (thank you Susanna)!

“We envision God’s Kingdom reality,” states the vision statement for the Wesleyan Holiness Women’s Clergy, “where the biblical foundations of gender equality are fully lived out across the Church as women and men lead together, following their holy calling.”

This organization of Wesleyan holiness women clergy includes leaders from The Church of the Nazarene, where I was raised, and The Salvation Army, as well as several other denominations.

Breaking down walls

In the book Women at the Crossroads, author Kari Torjesen Malcolm asserts, “The greatest breakthrough in opportunities for women to proclaim the gospel came with the Wesleyan revival in England in the eighteenth century.” These would include all subsequent expression of Methodism, such as the Wesleyan Church, the Church of the Nazarene, the Christian and Missionary Alliance, and The Salvation Army.

The most recent Church of the Nazarene manual states, “The Church of the Nazarene supports the right of women to use their God–given spiritual gifts within the church and affirms the historic right of women to be elected and appointed to places of leadership within the Church of the Nazarene, including the offices of both elder and deacon [emphasis added].” Essentially, the Church of the Nazarene believes that both Scripture and history affirms the role of women in Church leadership and in all positions. Since its founding in 1908, the Church of the Nazarene has ordained women.

In 2017, Dr. Carla Sunberg was elected the Church of the Nazarene’s second ever female General Superintendent—the highest elected position in the Nazarene church, overseeing the denomination.

The early practice of The Salvation Army is formed by its spiritual ancestry in the Wesleyan revival of the 18th century and of the pervasive influence of the holiness movement that grew out of that revival. The role of Catherine Booth, co–founder of the Army, was significant in promoting women in leadership and deserves particular attention.

Equalizing women in society

From the days of the early church fathers as shown in the patristic or early Christian writings, Dr. Roger Green, a Salvation Army theologian, argues that there has been an emphasis on the correlation between personal holiness and social responsibility, bringing significant societal benefits. “One such example of this is found in the success of Christianity with equalizing women in society.” These three emphases: personal holiness, social responsibility, and equality of women were foundational in the practice of The Salvation Army.

According to historian Dr. Edward McKinley, an influence on The Salvation Army in its earliest years in terms of inclusion of women in ministry leadership was that of the Quakers, who were members of the Religious Society of Friends.

“Booth found himself at the head of a rapidly growing movement badly in need of local leadership and funds,” wrote McKinley. “Women flocked to The Army, and Booth … used women in the entire range of Army work … almost from the very beginning. Catherine Booth, an extraordinarily intelligent and capable person, spearheaded this reform. The Quaker example proved, again, helpful and encouraging in this regard … It is clear that the early Salvationists repeatedly made eager use of the Quaker example in employing women in the Christian ministry.

“The unity of conviction on this point between Catherine and William was sufficient to overflow into their own practice within their marriage and into their leadership of the newly established Salvation Army.”

In terms of John Wesley’s influence upon The Salvation Army, it would be difficult to imagine a stronger statement than that of co–founder William Booth, who said, “I worshipped everything that bore the name Methodist. To me there was one God, and John Wesley was his prophet. I had devoured the story of his life. No human compositions seemed to me to be comparable to his writings … and all that was wanted, in my estimation, for the salvation of the world was the faithful carrying into practice of the letter and the spirit of his instructions,” wrote Booth–Tucker in 1892.

A passion for social justice

William Booth left the Methodist church while still a young man and established The Salvation Army, infusing his Wesleyan theological roots with a renewed evangelistic zeal and a fiery passion for social justice. Dr. Paul A. Rader, a former international leader of The Salvation Army, argues that the holiness movement itself championed women’s rights and female equality. Specifically, “Phoebe Palmer exercised extensive influence in the struggle for women’s rights … it was the evangelicals, and principally those of holiness persuasion, who championed the cause of female equality in church and society.” Palmer had a singular influence on Salvation Army co–founder Catherine Booth.

Dr. John Read, a Salvation Army minister and writer, underscores the significant, formative influences upon the early years of The Salvation Army. Methodism and Wesleyan doctrine and practice, various mid–19th century movements of renewal and revival (noting specifically the example of Phoebe Palmer and the Quakers), and surprisingly, popular culture.

Dr. Read wrote, “Freed from constraints of outdated and irrelevant ecclesiological and religious practices, the founders looked to the world for models and methods that would assist them in their God–given mission.”

The influence of Wesley, the Quakers, holiness doctrine, and the example of Phoebe Palmer, are all readily understood in terms of their historical influence in the empowerment of women in leadership as foundational to The Salvation Army.

However, given the context of 19th century England in which women were not empowered in leadership, and the strict standards of the puritan holiness lifestyle adhered to and preached by the Booths, the influence of popular culture is noteworthy. Historian and author Dr. Pamela J. Walker offers insight as to specific ways in which Victorian English culture and the early Salvation Army intersected, specifically regarding gender roles. The Salvation Army “disrupted and refashioned gender relations in many facets of its work … as Salvationist women challenged and resisted the conventions of femininity and enhanced women’s spiritual authority.” Further, in claiming the right to preach, women “disrupted a powerful source of masculine privilege and authority.” Walker concludes, “Virtually no other secular or religious organization in this period offered working–class women such extensive authority.”

Catherine Booth and inclusion

Much credit goes to Catherine Booth, co– founder of The Salvation Army, for the significant inclusion of women in leadership from the start.

In 1984, Norman H. Murdoch described it this way, “Catherine Booth recognized women’s powers of intellect and innate equality and elevated them to clerical parity with men. Although Catherine Booth did not break new hermeneutical ground in her discussion of scriptural support for the ministry of women, she did, through her public advocacy, force the introduction of thousands of working–class women into the ranks of ordained clergy.

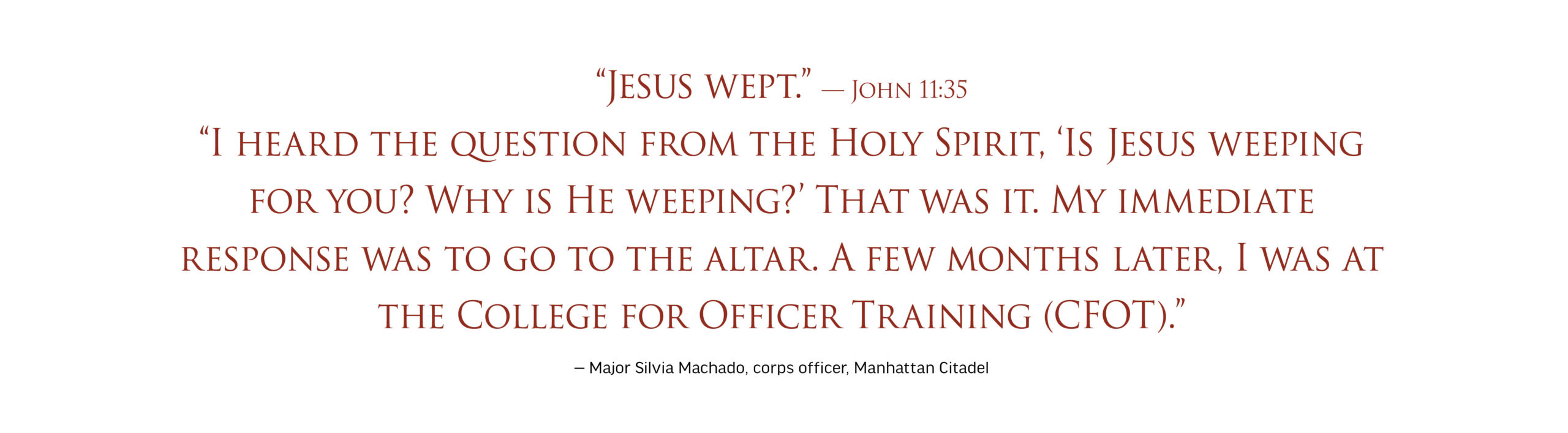

Stated in an article in Christianity Today on activists, it reads, “Catherine Mumford Booth’s book, Female Ministry, a short, powerful defense of American Phoebe Palmer’s holiness ministry, was not a plea based on natural rights or other feminist themes of the day. Instead, she founded her argument on the absolute equality of men and women before God. She acknowledged that the Fall had put women into subjection, as a consequence of sin, but to leave them there, she said, was to reject the good news of the gospel, which proclaimed that the grace of Christ had restored what sin had taken away. Now all men and women were one in Christ.”

William and Catherine Booth held strongly egalitarian views on women and men, radically so in the Victorian era. The following statement appears in the earliest founding documents of The Salvation Army—Orders and Regulations for Staff Officers of The Salvation Army in the United Kingdom in 1895, “One of the leading principles upon which the Army is based is the right of women to have the right to an equal share with men in the work of publishing salvation to the world … She may hold any position of authority or power in the Army from that of a Local Officer to that of the General. Let it therefore be understood that women are eligible for the highest commands—indeed, no woman is to be kept back from any position of power or influence merely on account of her sex … Women must be treated as equal with men in all the intellectual and social relationships in life.”

The deployment of women

The deployment of thousands of young women throughout Great Britain to advance the mission of The Salvation Army was a remarkable phenomenon in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Consider the following statements in Salvation Army foundational documents relative to gender equality:

First, from The Constitution of the Christian Mission, Section XII, which changed its name to The Salvation Army the following year, “Godly women possessing the necessary gifts and qualifications shall be employed as preachers … and shall have appointments given to them … and they shall be eligible for any office.” (Christian Mission Magazine, 1877)

Historically, The Salvation Army experienced explosive growth in no small part because of the involvement of tens of thousands of (mostly young) women in the mission of Christ. The release of these women into ministry was borne out of the influence other Christian traditions both ancient and relatively recent and was motivated both by theological and practical impulses. Further, the historical interaction between this burgeoning movement and 19th century contemporary culture was synergistic, each influencing the other.

The rule of Christ

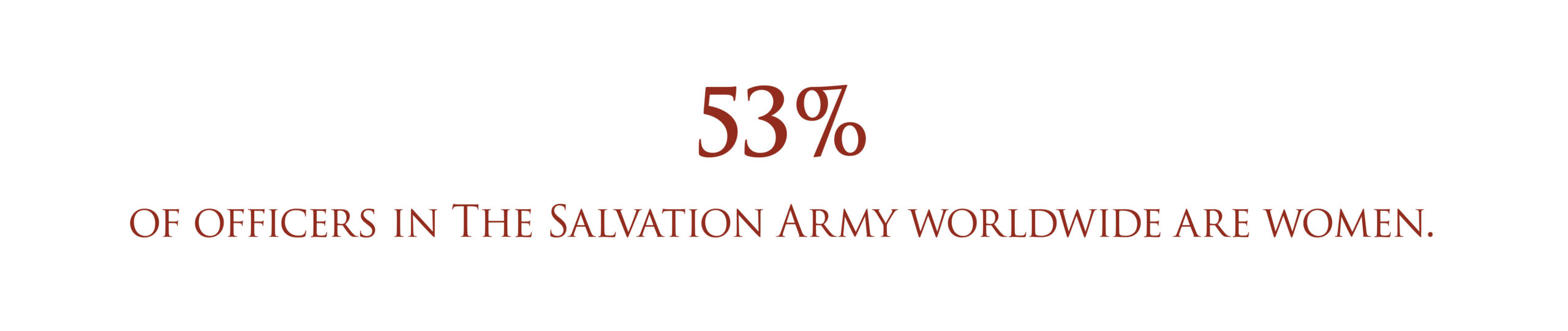

Contemporary statistics also make a strong statement regarding empowerment of women as demonstrated by ordained leadership within The Salvation Army. At the International College for Soldiers in September 2012, Salvation Army historian Dr. Roger Green noted that by percentage, The Salvation Army has more females in leadership than any other church, denomination, or Christian organization. For example, to date, 53 percent of officers in The Salvation Army worldwide are women. Thus, The Salvation Army has from its earliest days given ready opportunity to women to be trained, ordained, commissioned, and deployed in leadership locally and globally, and that continues to be true. Salvationists specifically, as Wesley’s theological descendants, need a continued intentional commitment to opposing injustice and advocating on behalf of the powerless, including women within our ranks, and serving alongside the same. This is a vital aspect of our identity in Christ.

What is the rule of Christ? Is it a theocracy, which legitimizes a hierarchy, or the authority of a value confined to religion and the inner life of the soul? The charismatic rule of Christ in the community is essentially liberation from the violence and the pressures of the “powers of this world.” (Jüergen Moltmann 1989)

A new generation of women

During my appointments as a Salvation Army officer—particularly my appointments to leadership at the International College for Officers, and as principal at two Salvation Army training colleges, I have shared life with hundreds of women, from a wide range of ethnicities, cultures, and ages. I am deeply grateful for the abundant opportunities afforded me to learn how to support women in their personal and vocational development.

I continue to be a witness to a remarkable generation of younger women in The Salvation Army—gifted leaders, clear and courageous in their commitment to matters of justice, double—portion “daughters” in whom I take great delight!

For such a time as this

What might this mean for you? How can you participate in strengthening the significant legacy of equal opportunity for women in The Salvation Army, in your church or in your place of work? What opportunities are yours to empower others and to accept the invitation to join in? What words of God will you use to help stir the hearts of both men and women to serve Him? These are important questions for the time we live in today as we strive to become one in Christ.

Read more from the latest issue of saconnects.