The Farm Colonies

by Robert Jeffery

The year 1890 was a milestone in the history of The Salvation Army. It was, as Charles Dickens might say, “the best of times and the worst of times.” The worst of times as The Salvation Army was mourning the loss of its mother—Catherine Booth who was “promoted to Glory” after a long battle with breast cancer; and the best of times as The Salvation Army launched a new book that hit the publishing world by storm. In Darkest England and The Way Out, written by William Booth, revealed Booth’s plan for salvation in any season.

In reformist circles, the book was both hailed as a success and soundly criticized. Some viewed it as an amazing blueprint that would solve all the ills of society while others saw it as overly simplistic and unfeasible. Among one of the many ideas Booth floated to address poverty and overcrowding in cities was the creation of work farms in the countryside, or as he called them, “Farm Colonies.”

The Booths came of age in a time of history known as the Industrial Revolution when new technologies radically changed the manufacturing industry. Things that were once produced on a small scale, or by hand, could now be made in factories at much higher levels of production. The rise of the factory workplace required an almost endless supply of workers. Seeking new opportunities to better their lives, men and women from rural Britain poured into cities such as London and Manchester to take up jobs in these factories.

In some cases, entire families moved into the cities which were already suffering from overcrowding and a lack of affordable housing—only to find themselves in the worst economically depressed neighborhoods, then called slums. Other families remained in the country, while one parent (usually the father) moved into the city, to support his rural family from afar. In either case, family life was severely upended by the Industrial Revolution.

It could be argued that an increase in alcoholism, human trafficking, and crime in the city, were the unintended outcomes of this change to the way people lived and worked. For the first time in England’s history, many people who now lived far away from their home parishes, cut ties to the Church, forever turning their backs on their religious upbringing. This was the East End of London—with its gin shops and opium dens—where William and Catherine Booth found themselves in ministry.

Since the negative aspects of city life were viewed as the reason for people’s fall into ruin, the country was viewed by reformers as a potential solution. Or in other words, if humans were degraded by the conditions of the urban slum, perhaps they could find their redemption in the idyllic fields of the countryside. Where cities needed rural farms more than ever to feed growing populations, the idea of the farm colony easily took shape.

How did the farm colonies work? Laying out his plan in Darkest England, William Booth wrote:

“My present idea is to take an estate from five hundred to a thousand acres within reasonable distance of London. It should be of such land on it for brickmaking and for crops requiring a heavier soil. If possible, it should not only be on a line of railway … but should have access to the sea and to the river.”

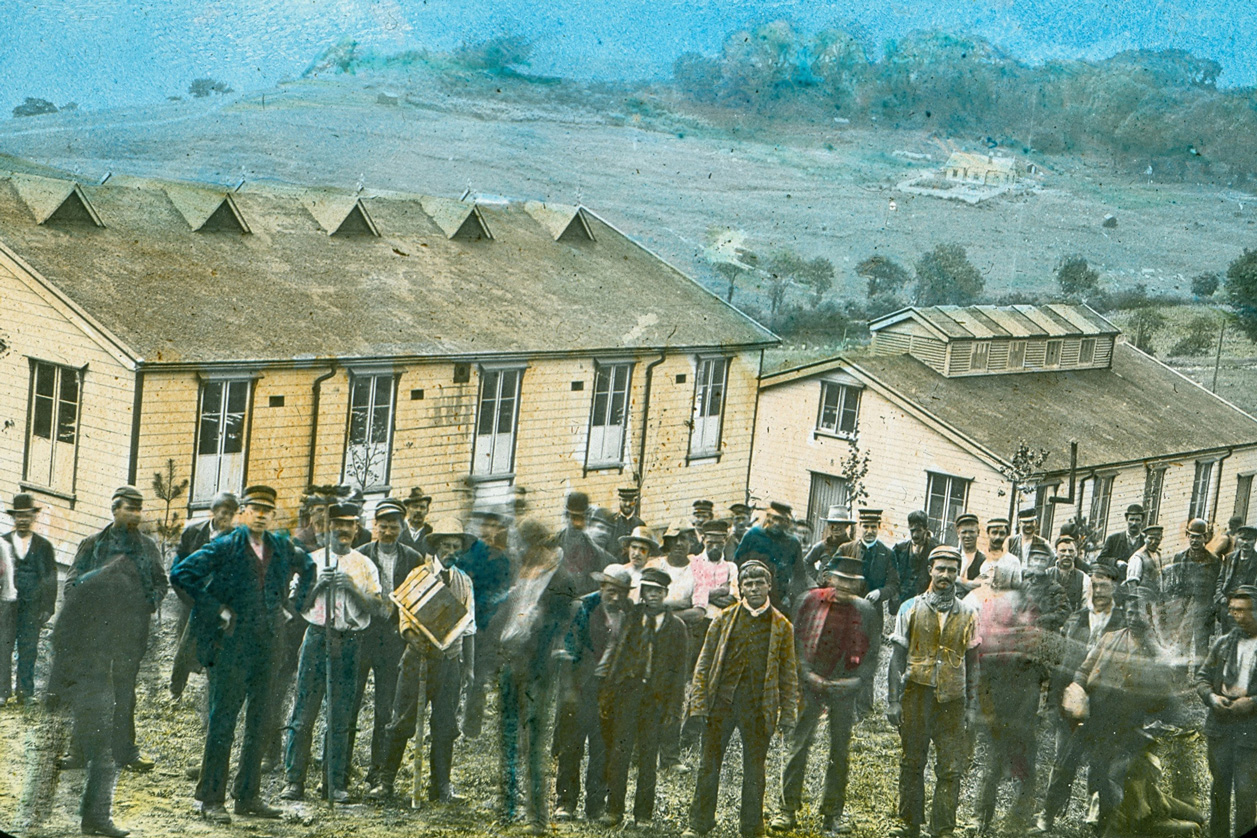

Booth imagined a workable farm staffed by men from the city, who had their roots in the country, and could thereby make an honest living in working the land. The best example of the Founder’s plan was realized in the Hadleigh Farm Estate, a Salvation Army run farm colony created in 1891 in South–East Essex on 900 acres of land. Hadleigh Farm is still in operation today – a commercial farm where people learn valuable skills around land management and animal husbandry.

In the United States, the idea of the farm colony took root in 1897 when 350 acres of farmland near Seattle, Washington, was gifted to The Salvation Army. Commissioner Frederick and Emma Booth—Tucker, the national leaders, seized upon the idea that maybe this land could be used to lift men and women from the cities out of poverty, enabling them to make a living. The Salvation Army would charge a reasonable rent to the tenant–farmers to make it a self–supporting enterprise.

In the Booth–Tucker’s plan, a single family would work a 5–acre plot of land in a farm colony between 100 and 1,000 acres. Frederick Booth Tucker, who dreamed big, later envisioned farm colonies of up to 100,000 acres all over the U.S. Some initial fundraising was required to purchase the land, but the Army had great support from various people of means who saw the value in the farm colony plan.

In total, The Salvation Army operated three farm colonies in the U.S.; the first in Fort Romie, California; the second in Fort Amity, Colorado; and the third in Fort Herrick, Ohio. Clark Spence, who wrote extensively about the farm colonies in his book, The Salvation Army Farm Colonies (The University of Arizona Press, 1985), noted that, in total, the three settlements included 1,400 acres of land occupied by 160 colonists.

Unfortunately, the farm colonies were not the financial success they were hoped to be. To pay the mortgage on the land, The Salvation Army required the colony farmers to give them a rent from their produce, however modest it might be. However, this seldom happened as many tenants proved not to be successful farmers. Some simply abandoned their plot, which required the Army to find new tenants.

However well intentioned, the farm colony enterprise had proved to be a costly boondoggle, though there are instances of many individuals who achieved some success and betterment of their lives. Fort Romie, the last colony and the most successful of the three, ceased operations in 1910 when the remaining families paid off their loans to the Army and became owners of their land. This must surely be considered a success!

Although The Salvation Army never again attempted farming on a large scale, recent years have seen the rise of the community garden, where people in cities grow fruit and vegetables on small plots of land, with the proceeds going to support their family or the local Salvation Army foodbank. In both large cities and small towns, the Army continues to acknowledge the growing food insecurity that affects many American families. In doing so, the importance of providing good, healthy, and locally grown food, while enabling people to produce food for themselves is recognized, which was at the heart of William Booth’s farm colony idea.

Read more from the latest issue of SAconnects.